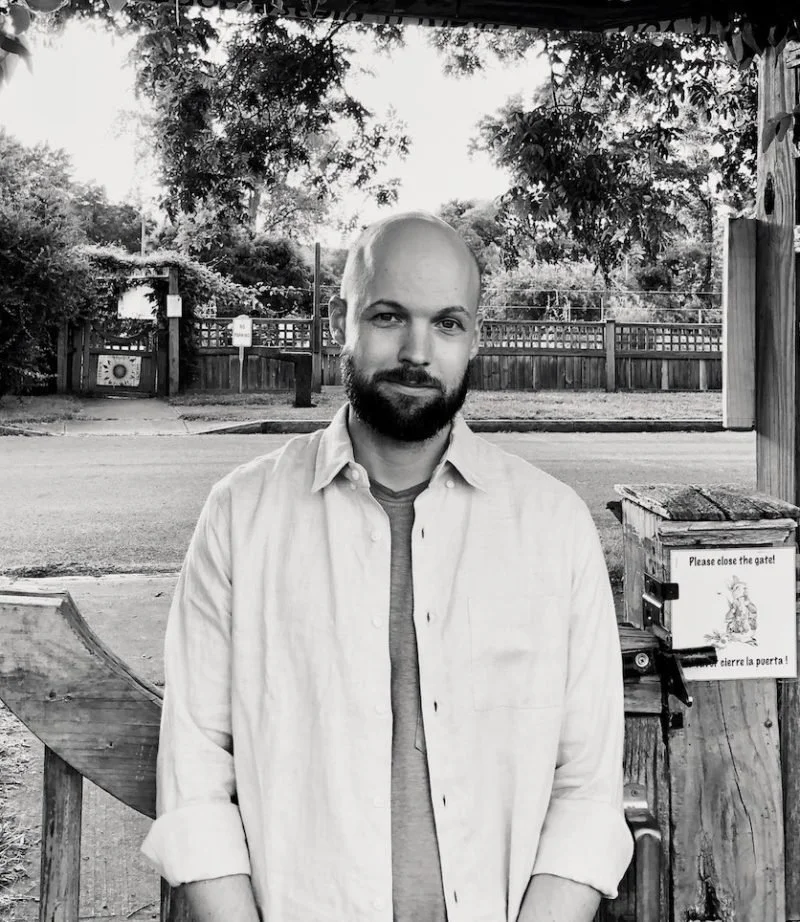

Mikko Harvey's sophomore collection, Let the World Have You (House of Anansi Press, 2022), is a touching and tender surrealist romp. From the macro (like his poem about another planet complete with a whale on fire) to the micro (like his poem about a blue worm on a wall or another that begins with a ladybug on a nose), this is a meaningful and inventive book. If Harvey's first book was (masterfully) experimenting with the possibilities of narrative poetry, then his second book is further honing in and building out this signature and original style.

Since interviewing Harvey in 2018, we’ve stayed in touch (he helped significantly with my recently released collection), and I felt it only right that he be the * first * author I’ve interviewed twice on this site. Four years later and my how we’ve grown. Grab his newest collection and read the feature below as you impatiently wait to track the shipping.

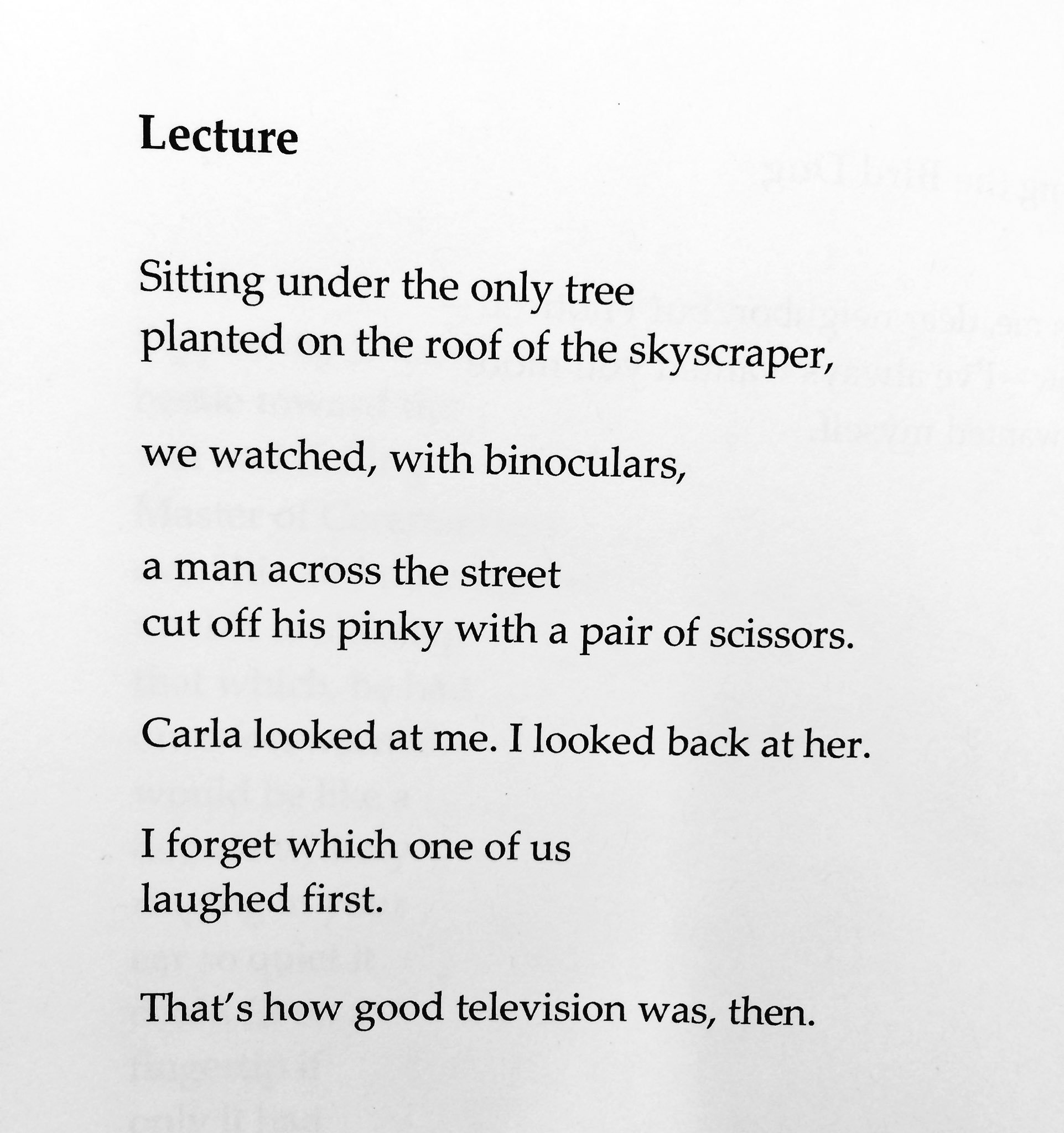

via Let the World Have You

You're the first writer I've interviewed twice on my website. Welcome back and congrats on your second collection of poems! You and I have talked a great deal about first books, and you really helped me with numerous "first book" resources including quotes and links, etc. How is this second book (formation, routine, style) similar and/or different?

Thanks for having me back! I hope I’m the first of many return guests.

In terms of formation and routine, one difference is that many of the poems in Unstable Neighbourhood Rabbit went through poetry workshops, whereas none of the poems in Let the World Have You were workshopped. I wrote many of the poems in LTWHY at artist residencies, which was not the case with UNR. And as a result I was meeting lots of different types of artists, which perhaps—I hope—influenced LTWHY in some semi-conscious way. I think I wrote fewer poems during the years of LTWHY’s formation, but a higher percentage of the poems were worth keeping. A handful of poems in LTWHY were written using a collage approach, with disparate fragments gravitating toward each other over time until they added up to a poem, whereas all of the poems in UNR were written using a more linear approach. In terms of style, I think of UNR as being more bold and sharp and LTWHY as being more subtle and liquid. There is a lot of violence in UNR and not much in LTWHY. I remain unable to stop writing poems about animals, so the two books are similar in that way.

In your 2020 interview with periodicities, you mentioned how your first book was written in your twenties and how you were hyper aware of having a debut at such a young age while simultaneously not rushing the process. Now that you have two books out, do you look back on these "debut" poems with criticism or curiosity or different eyes?

It’s weird to read my first book because I feel so distant from the version of myself that wrote it. But it’s weird in a good way, mostly. I find it endearing to think of that younger version of myself being so earnestly committed to funneling his imagination into narrative form, as he did repeatedly in UNR. He may not have known much about the world or even about himself, but he was pretty damn sure he wanted to funnel his imagination into narrative form.

I’m also struck by how cohesive UNR feels. I don’t mean that in a positive or a negative way, but I do think, partly because I was so young while writing the book, I leaned into certain aesthetic positions as a way of forming a poetic identity that felt solid, because that solidity felt like a protection against my own uncertainties, which in turn created the effect of cohesion.

Also, some of the poems I used to think of as the best poems in UNR I now find myself less interested in, whereas some of the poems that felt almost like afterthoughts at the time I now find myself most drawn to. But I don’t want to name any names, because I’ll probably just end up switching back to my original feelings eventually.

Do you see book two as picking up where book one left off? Sequels or siblings? Or something different altogether?

It’s more fun to think of them as siblings, but sequel is probably more accurate. Maybe half and half? In some ways the second book feels like a reaction to the first book, so maybe that’s what it is, a reaction, the way in chemical reactions one event has to take place before another one can, in distinct but linked phases.

I’m sorry for probably butchering that, scientists.

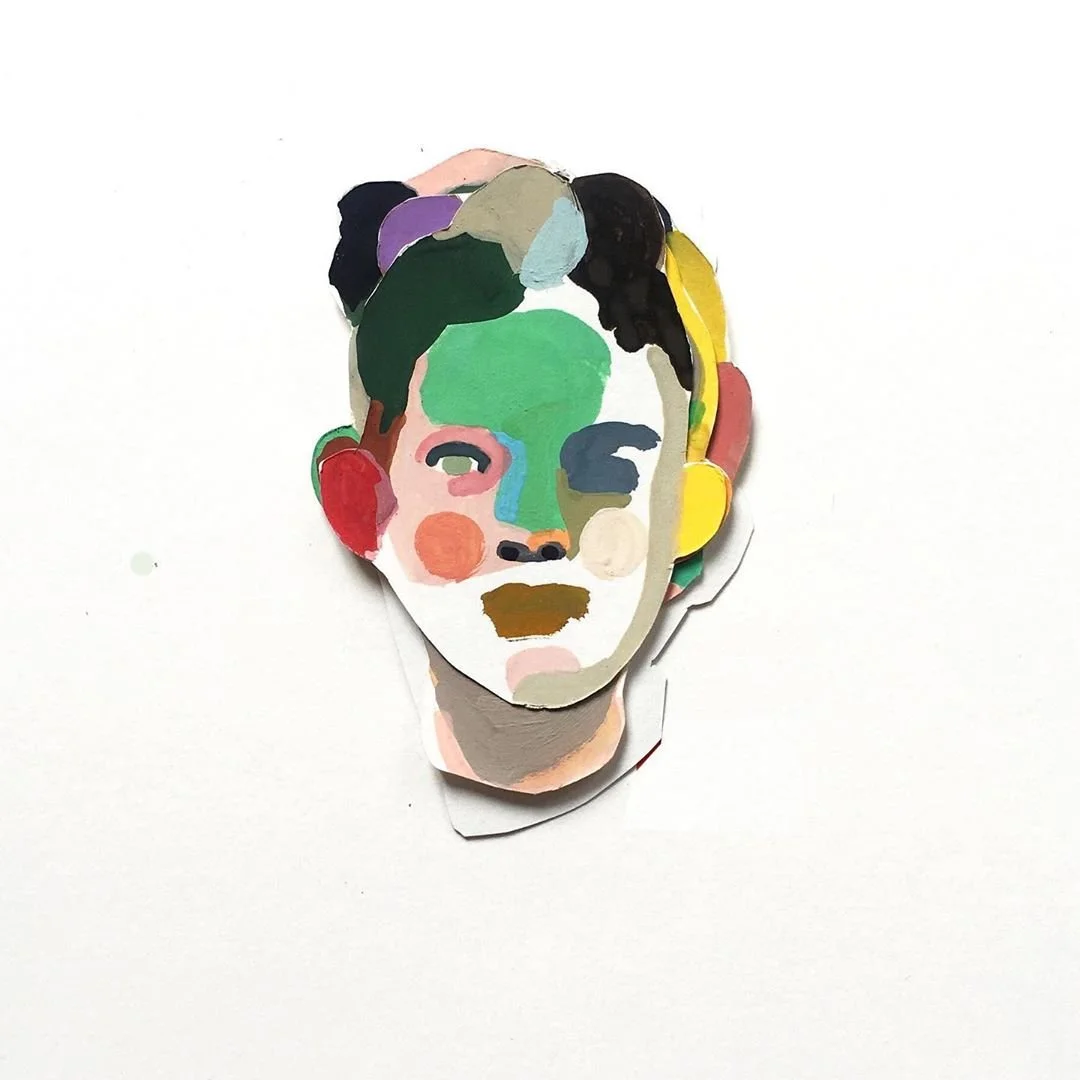

art by James Siena

I'm curious about the cover. A little over a year ago, you asked me about some art and possible covers you were considering. Can you speak on this design selection? Did you always want to have more of an abstract texture?

I sent the designer at Anansi—the super talented Alysia Shewchuk—around ten images to consider using as cover art. It was a mix of abstract paintings, representational paintings, collages, and photographs. Based on those images, Alysia created three cover options. I received the options in an email while I was walking across the Rip Van Winkle Bridge.

I was torn between two of the options and became obsessed with the decision. I’ve recently been looking for a new apartment and that decision felt similar. When you visit an apartment you like, then you visit another apartment you also like, two paths forward open up that are completely different but both viable. You can almost feel your two future lives hanging in the air, and you have to choose one while forsaking the other. You can ask for advice, you can make lists of pros and cons, but at a certain point you just have to shrug your shoulders and make a funny little human decision. Fortunately, I think we ended up with the perfect cover in the end, which features the painting Converbatron by James Siena. I like how from a distance the cover looks like a soft purple glow, but the closer you get to it the more you notice the tiny, intricate connections that create the effect of that glow. Not unlike reality. Plus I’ve always liked the color purple.

Along with the cover, the book opens and closes with a square graphic resembling the cover, but also resembling a fingerprint or the rings of a tree. Care to elaborate on this?

I asked for a visual marker to begin and end the book, something to separate the poems from their more businesslike neighbors: table of contents, acknowledgements, etc. I like the idea of the graphics functioning sort of like a big parenthesis and the poems living in that enclosed space. But the specific design of the graphic was purely an Alycia call, one that I simply liked and accepted when she sent it to me. I like how there’s a writhing quality to it, but the writhing is contained within the formality of a square. And I like the fingerprint and tree ring associations you mention. In fact I just started Googling tree rings and now I kind of wish I’d asked for a tree ring instead. Maybe next time.

I also love that both of your books are not divided into sections. When you start, you keep going until the book is over. There's time to breathe with the white space, but no section breaks or additional titles. As someone who is constantly creating subsections and micro-titles, I really find your method refreshing. Were sections attempted at one point and then scrapped, or did you always plan this kind of concision for your collections?

As the writer of the poems, I see them as adding up to one big uninterrupted poem forest—or one big uninterrupted poem forest with a single trail running through it, the trail being the order of the poems. It only felt right to try to present the reader with a similar experience. Not that I believe this is necessarily the best way to organize books of poems. Many of my favorite poetry books use sections and subsections and do so in fascinating, almost architectural ways. I’ve just always felt that my own poems lent themselves to a more open approach. What appeals to me is presenting the poems without any directions—I’ve never felt like much of a director—except for the directions found in the poems themselves. Maybe it’s the same reason I don’t do epigraphs or dedications. I did briefly try dividing my first book into two sections, but ultimately those sections didn’t feel meaningful enough to justify the intrusion, so I let them go. With my second book I knew to not even try.

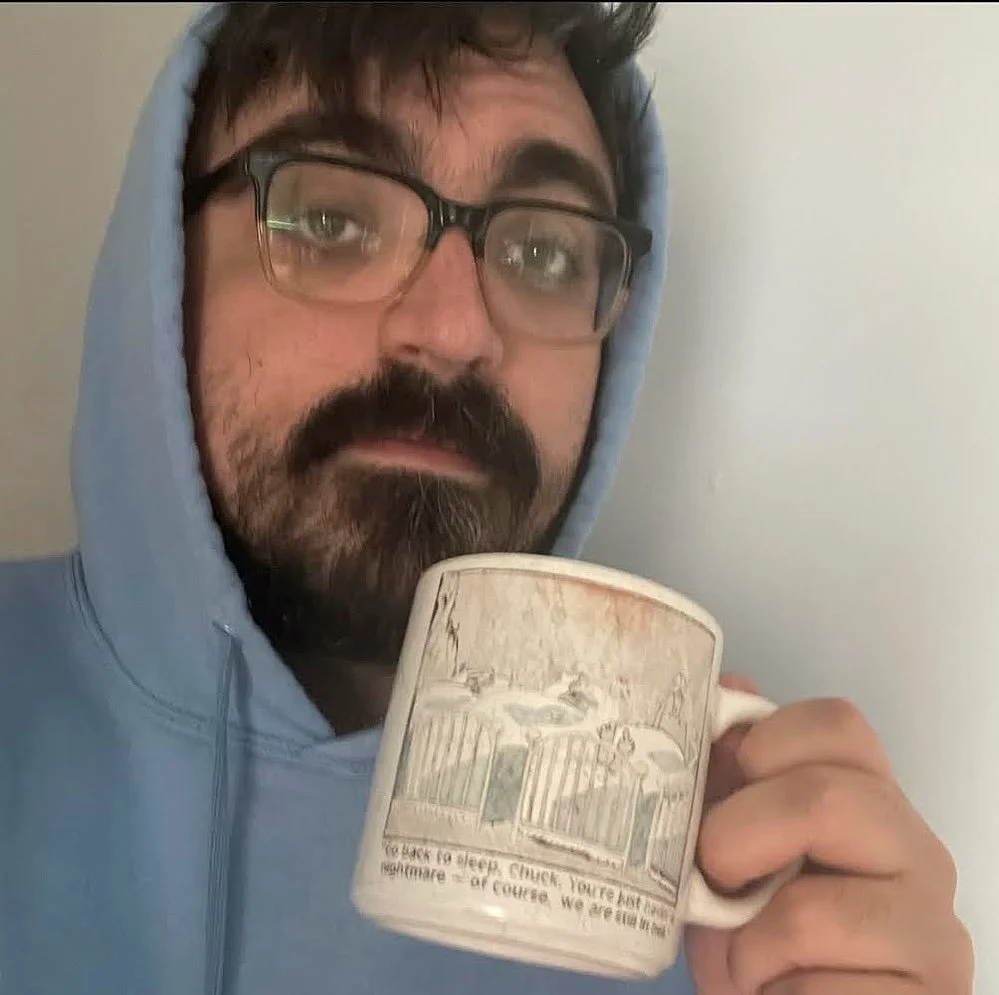

via Idaho Falls with Jake Bauer

In between your two full-length collections, you released two collaborative chapbooks with other poets. How does collaboration play into your writing life? Are you writing alongside/with any other poets at the moment?

I continue to collaborate with Miss Expanding Universe on various kinds of writing, which mostly takes the form of private creations but occasionally we stumble into something at least semi-suitable for public consumption, such as SkyMall. Jake and I are on a collaboration hiatus but I hope we get back into a collaboration rhythm one day. We wrote Idaho Falls while we were roommates in Ohio, and the in-person element was essential to the growth of the chapbook. Hopefully we’ll find a way of collaborating that can be similarly rewarding but from a distance. I love collaboration for many reasons, but one of the big reasons is that it helps me escape the trap of being too intentional, too attached to the illusion that I am in control of where my poems are going. I don’t think I’ve ever written a good poem that I felt I fully controlled. The poem needs to be out ahead of me, pulling me along rather than being pulled along by me—and good collaborators provide this quality automatically. My collaborations have been some of the most joyous experiences of my writing life. I think, if some art god decreed it must be so, I could probably be happy never writing my own poems again and only writing collaborations.

"I actually started writing new, post-Unstable Neighbourhood Rabbit poems in 2016, before I even submitted the manuscript. There was an awkward phase that lasted a year or so during which, whenever I wrote a poem, I had to ask myself: is this a rabbit poem, or a post-rabbit poem?" You started writing "post-rabbit" poems in 2016, before submitting your debut manuscript. By the time your sophomore collection was finished, were you already onto book three? In other words, what are you currently working on?

To be honest, I’m not really working on poems at the moment. I know I said this in our last interview too, and it turned out to be kind of a lie, but this time I really am trying to move more slowly, and I think it’s going to be a nice long while before I have another book. I have a few new poems and a bunch of disconnected fragments, but there isn’t a clear guiding impulse pointing me toward a new book yet. With my first two books, I found that guiding impulse early in the process, and it both pushed me forward and directed my forward momentum. And in both cases, the guiding impulse felt psychologically urgent, like I needed to be writing those exact poems in order to clarify certain essential yet murky parts of my life. Until another impulse like that begins to emerge, I can’t think about book three. But I’m enjoying the break. I’ve been writing poems pretty continuously and obsessively for the last decade or so, and in a weird way it feels like not writing poems is the most poetic thing I can do right now. Also, I want my new poems to be quite different from my old poems, and I think letting some time pass will encourage that change. Only a mongoose can change directions without slowing down.

Despite your sophomore collection being released in 2022, I'm going to assume most of these poems were written pre-COVID? During lockdown, did you see your writing being influenced by the pandemic at all? Given this timeline, I like the idea of a Mikko Harvey pandemic collection dropping in 2026.

About two thirds of the poems were written pre-pandemic and one third was written in-pandemic. I don’t think the pandemic changed the direction of my poems so much as it pushed them deeper into the grooves they were already inhabiting. I was living in Ithaca, NY when the pandemic hit. I found the way the city and the landscape intermingled in Ithaca to be generative for my writing. I lived next to a waterfall and I would go there most days, look at the falling water for a few minutes, then go home. The arboretum was also important. The dramatic views and gorges. The deer. The hawks. The groundhogs. When the pandemic shut everything down, these nature experiences stayed open and I leaned on them, and they fed my poems.

Also, I’ve always been shy and retreating, and I’ve always felt a tension between my shyness and my desire to be braver and more outgoing. The pandemic, by removing the option of being outgoing, messed with this tension. It was like, “Oh, you like cupcakes? Eat one hundred cupcakes right now then. And for the next year you can only eat cupcakes.” While eating those solitude cupcakes, I started to see more clearly how much of my life I’d spent hiding and resisting connections. I think that realization found its way into my poems. In fact that’s where the title of the book came from: “let the world have you” began as just a note I wrote to myself, a little reminder to be more open and let my guard down. The phrase got stuck in my head and never left.

With this new collection, I see your poems as both more macro and more micro. You have a fable about another planet (complete with a whale on fire) and you have the line "demonstrating myself to the universe" but you also have a poem about a blue worm on a wall and another that begins with a ladybug on a nose. Inspecting pollen, noticing leaves, digging deeper, while also expanding outward and looking into the vast expanse. Does this resonate with you? How do you see these methods as interacting/colliding?

This definitely resonates with me. It makes me think of the Dean Young lines “Do not confuse size with scale: / the cathedral may be very small, / the eyelash monumental.”

The other day I was driving on the highway, my attention on the road and on my thoughts, when I noticed some indistinct flicker in my line of vision. When I looked more closely, I realized there was a tiny spider clinging to the outside of my windshield. It was clinging there while my car moved through space at 70 miles per hour. It was far from home. I like how that spider’s trial—physically small but actually quite epic—was unfolding in my presence for like an hour before I finally happened to notice it. It’s so chancy, the little things we happen to notice and the little things we don’t. I like that chanciness. It’s like a built-in surrealist technique.

Your question also makes me think of seeing the Giacometti show at the Guggenheim Museum in 2018. I remember being delighted by the way his large sculptures—tall and skinny, towering over me—would often be placed right next to his miniatures. I loved that toggle, and how as a viewer I had to adjust while moving between the macro and the micro. That day I decided I wanted to have at least a few tiny poems in my next book, existing in close proximity to much larger ones.

As with all of my interviews, I ask for a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you like. Here is your prompt for our previous interview: Write a poem immediately after watching (or even while watching) a good movie. Or a play or a concert or the season finale of a TV show—anything that gets your brain moving quickly and complicatedly. I find that sometimes a poem can piggyback off of and tumble right out from that energy.

Record a voice memo on your phone and send it to your friend. It’s okay if it isn’t a poem. Just go for a walk and start speaking without a plan, saying whatever enters your mind. Try to fill between ten and twenty minutes (any longer and the attachment gets too big to send as a text message).

In closing, do you have any final words or shout-outs, pieces of advice? Thanks so much for taking the time, Mikko!

I would like to shout-out neonpajamas for being such a curious, generous, and perceptive reader, thinker, and writer. I would like to advise society in general to support neonpajamas in his ongoing efforts.