Graham Foust is a Colorado-based poet and translator and educator. He has released eight collections of poetry, most recently Embarrassments (2021) and Nightingalelessness (2018), both released through Flood Editions. Sparse yet dense in vocabulary, his poems hone in on the line and the word and the syllable and the intricate rhythms connecting the dance. Like breathing through a tongue twister, Foust’s poems are musical out-of-body meditations. The kind of poems to have in your backpack at all times. The kind of poems to make you burn your manuscript and start anew.

For three months, Foust and I emailed back and forth, a few questions and answers at a time, a wedding in between (mine), a summer break in between (his), during which this was his automatic reply:

It's summer, so I will be checking email less frequently than usual, and this is the auto-reply that says so.

Here's an Alan Dugan poem to tide you over:

SUMMER GALE

This is my last

message for a while:

all dates are off.

The wind is high,

time is nearly up,

everything is blowing

monarchs to pieces,

so bye bye butterflies.

What a process

of common disintegration.

Goodbye, I might

be back from where

the wind is blowing

but not in time.

During our correspondence, we talk process, collage art, 80s movies, The Psychedelic Furs, breaks from writing, and much more.

I always like to begin with an icebreaker: Find the stack of books nearest to you. Select the book that's exactly in the middle of said stack. If you could, provide the title of the book and a little anecdote you may have to go along with it. If no anecdote exists, please open the book at random and type out one sentence.

Carlo Crivelli by Ronald Lightbown (Yale University Press, 2004). I recently read an article about Crivelli in the London Review of Books, but the reproductions in the article were quite small, so I got this book from the library to see larger versions of the pictures. That’s likely a boring anecdote, so here’s a detail from his painting of Saint Lucy.

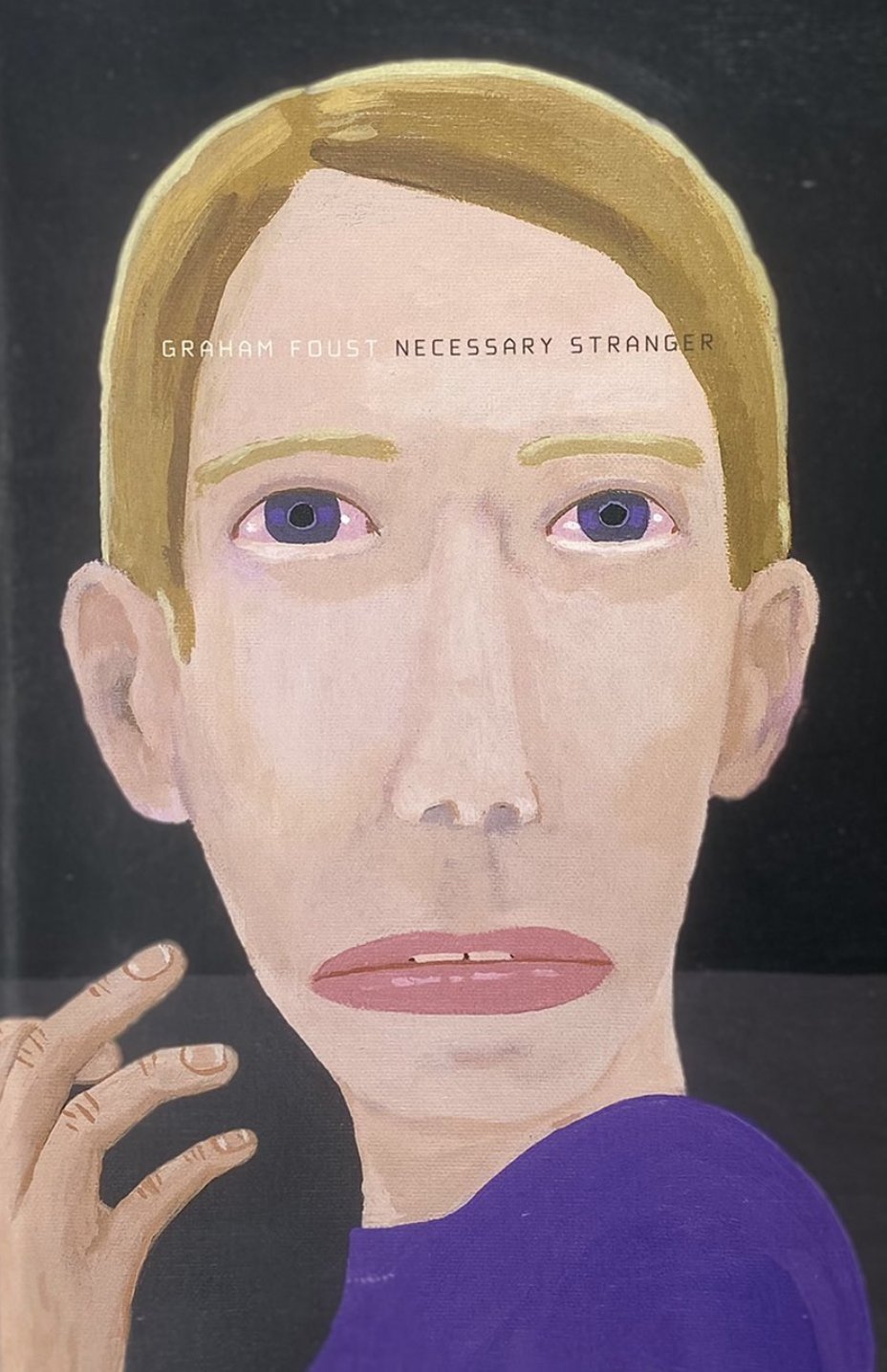

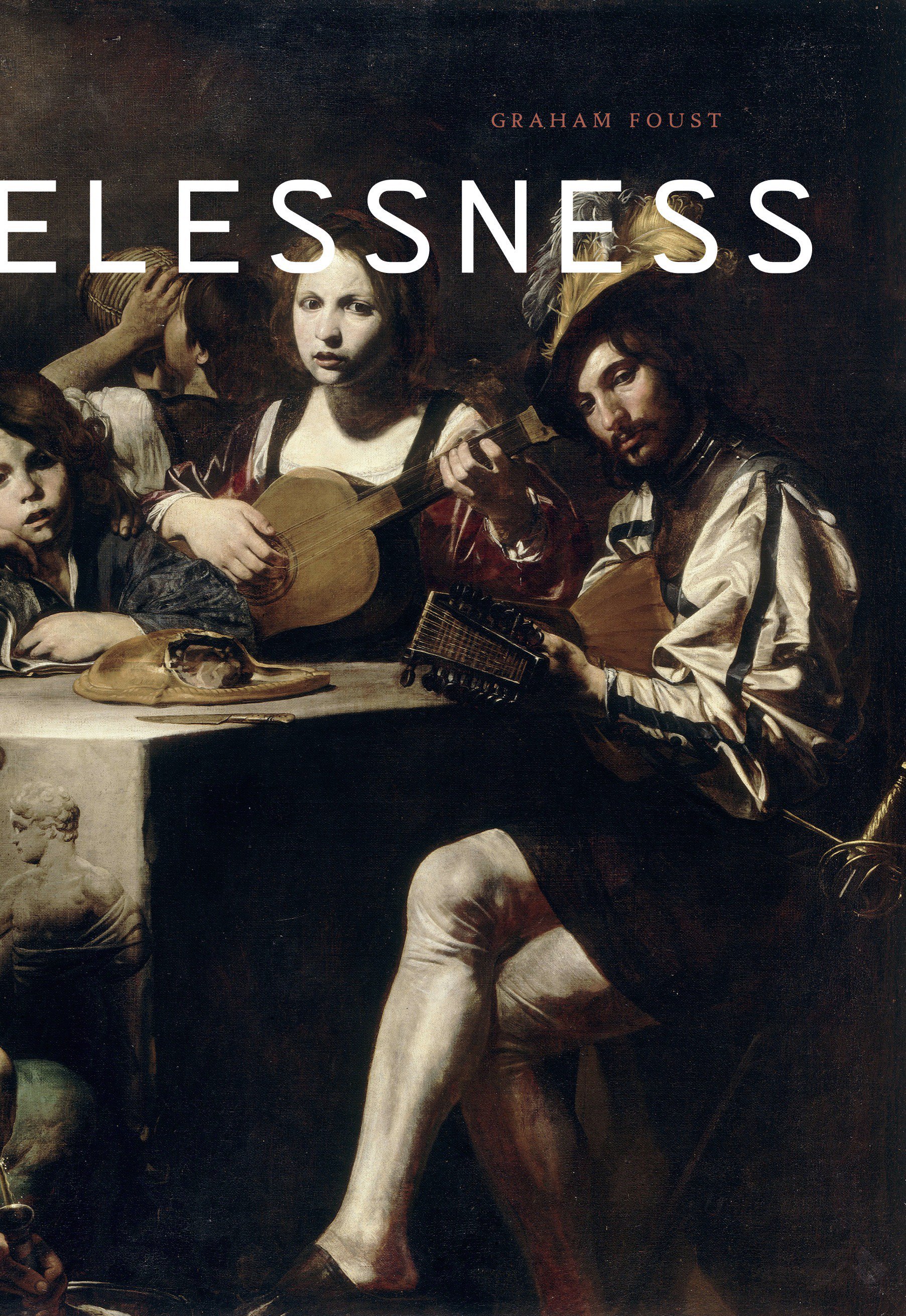

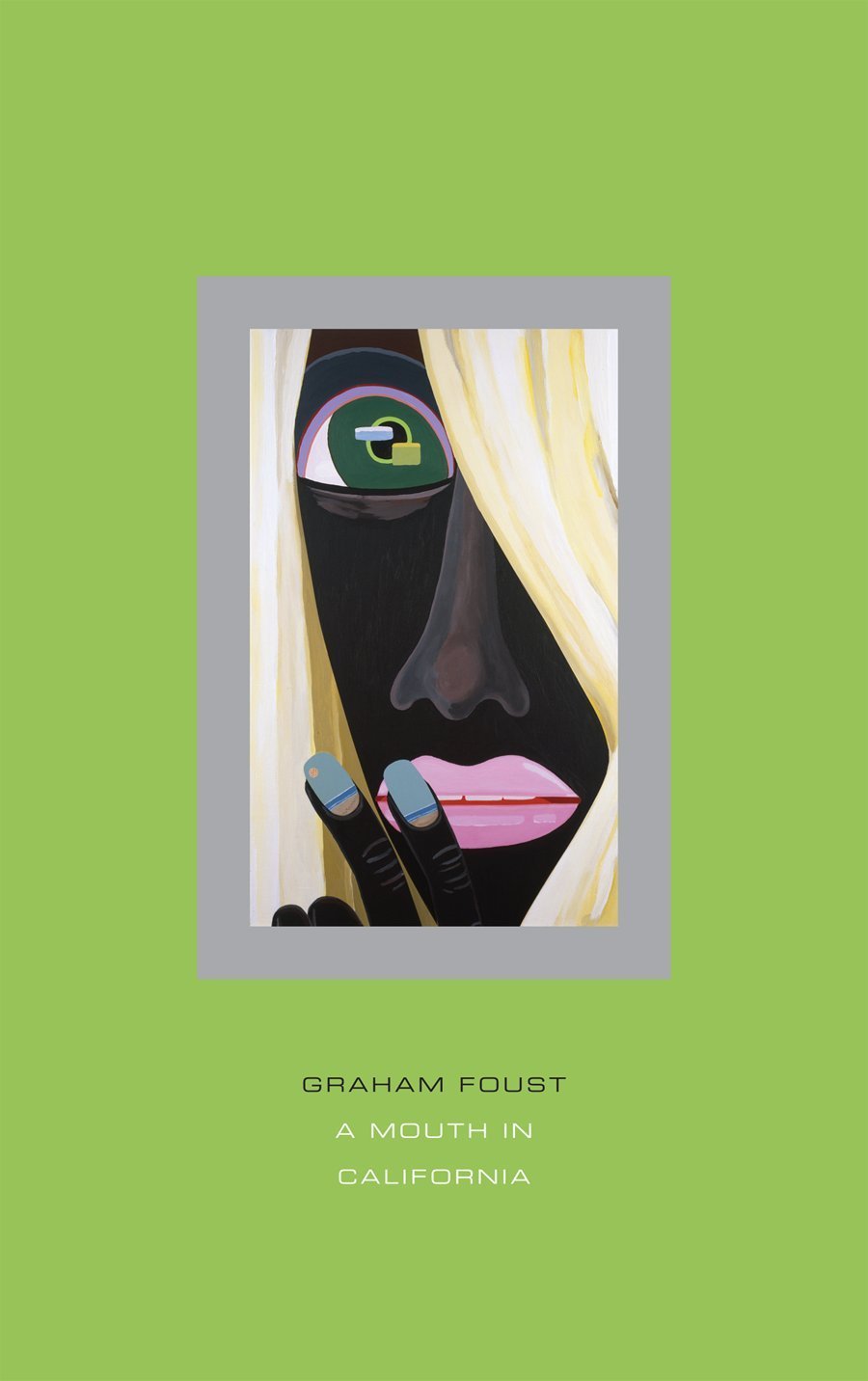

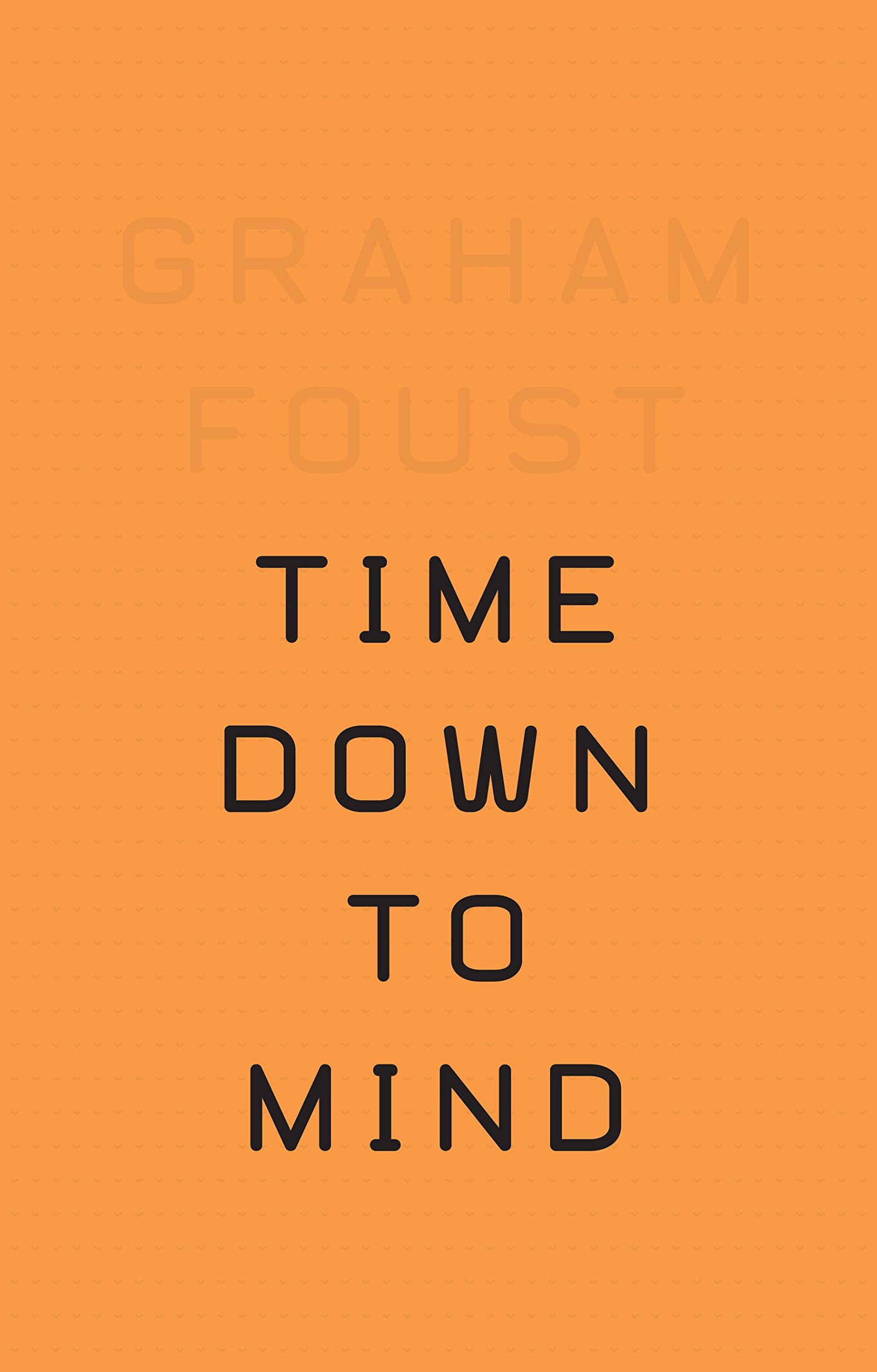

Are those eyes on a plate?! I looked up the full painting, and I can't tell if the eyes are sleepy or dying or simply looking up. Painting and visual art seems to be not only a big part of your books (the stunning covers, my god) but also your personal life. Are your tastes rather eclectic or do you find yourself returning to a certain period/era?

I believe they’re Saint Lucy’s old eyes, which were gouged out—by her or by someone else, depending on which version of the story you’re reading—before God gave her new ones.

My tastes are pretty eclectic, though as I’ve gotten older I’ve found myself more interested in older art. This is due in part to my love of Michael Fried’s writing, which is deeply learned and scarily incisive.

Do you yourself paint?

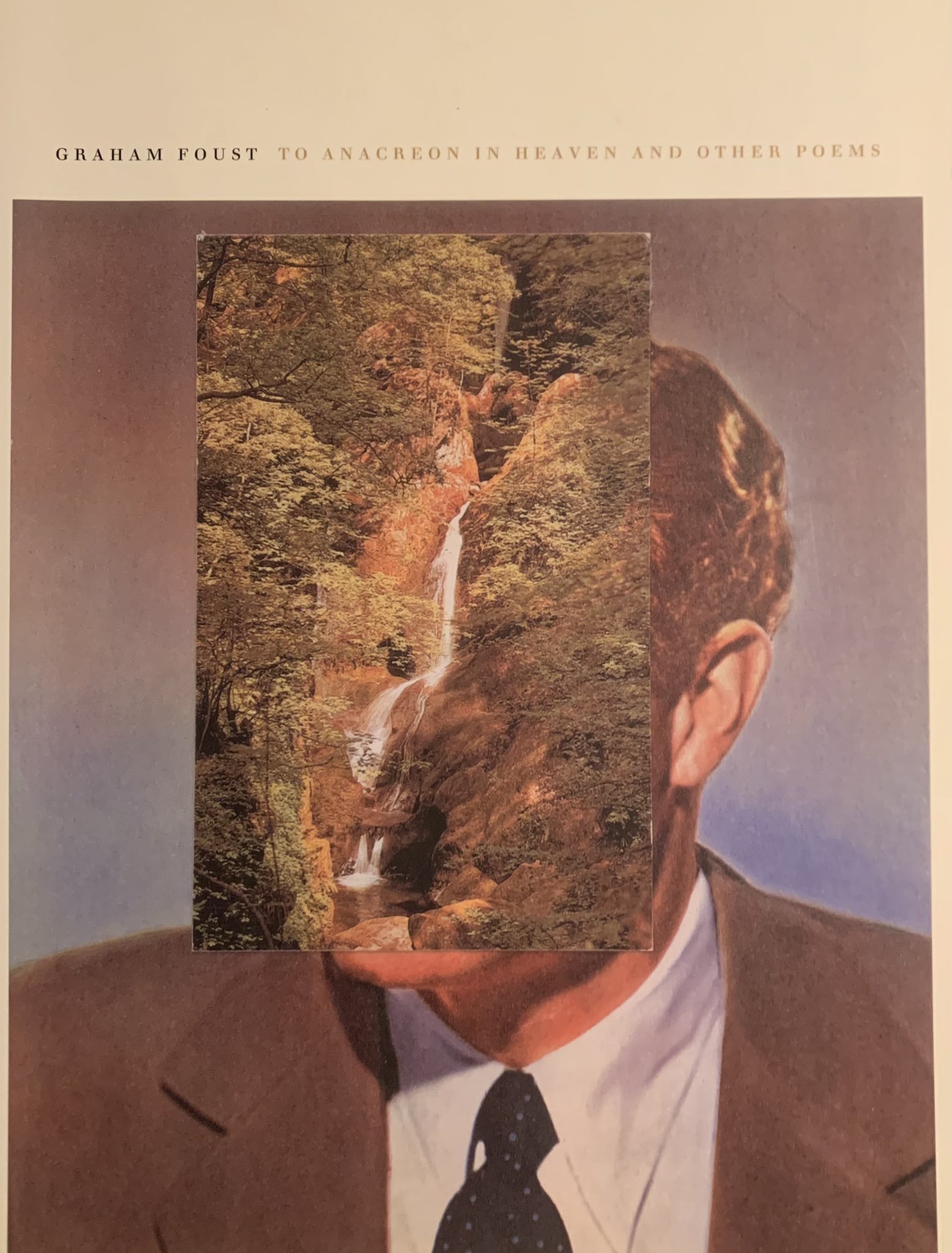

I’ve made visual art for at least as long as I’ve been writing, but mostly on the down-low. I make collages, take photographs, and paint. I send pieces that I think are good to friends and throw the rest away. Here are a couple:

I looked up the release date of your most recent book, Embarrassments, and it was May 11, 2021, a year and four days before we started this correspondence. First of all: congrats on that release! Can you talk a little bit about how it was assembled and finalized? Obviously releasing a new book during a pandemic offered its own difficulties. Did this one see a delay as a result?

Thank you. Embarrassments was finished before the pandemic began, and so it didn’t really affect the writing or the assembly of the book. As to its publication, I don’t think it affected anything on the publisher’s end either, or at least not that I remember. I feel like it came out when they said it was going to come out.

From my perspective, releasing a new book during a pandemic seemed far easier than, say, sending my kids to school.

Was every poem in Embarrassments (2021) written after Nightingalelessness (2018) or do you find yourself digging through past archives when working on "new" material? In other words, when one chapter or era closes, does another begin, or is it more cyclical for you? Is it all one long dream? In other-other words, how do you compartmentalize and organize/arrange a collection of poems?

I tend to write one poem at a time, so yes, every poem in Embarrassments was written after the poems in Nightingalelessness. But I would guess that I mined failed poems that didn’t make it into Nightingalelessness but were still extant in a notebook or a printout for things that could be of use while writing new ones. That said, I have no specific examples I can cite—that part of writing is usually a blur.

My process for putting together books hasn’t changed much over time. I don’t write anything for a long time, then I usually have a three to five month period where I write quite a lot. This cycle repeats itself a few times, after which I sit down and figure how the poems that I’ve written fit together.

In regards to your writing process mentioned above, do you find it to be compartmentalized with minimal overlap? For example, when you're ordering/arranging, you're not writing new poems? And when you're writing new poems, you're not ordering/arranging?

That seems more or less accurate to me, though I always seem to slip a new poem or two into a book late in the game.

I've heard some writers say that if they don't write (every day, every week), they don't feel like themselves. In opposition, Mary Ruefle once told me, "Farmers will leave a field fallow for a year to reintroduce nutrients to the soil. The soil will grow stronger." Going long stretches without writing, do you find yourself more nourished when you return to the page? During this "fallow period," as Ruefle calls it, do you find yourself reading/researching/focusing on poetry or redirecting instead to other hobbies/interests? Is your inner poet still mumbling lines and writing on napkins?

I don’t write every day. There are plenty of other things to do.

But I’m always reading, so in that sense I’m always writing, which is to say that I’m making notes, scribbling down things I think I might be able to use, and, yes, mumbling. And I teach literature for a living and write prose about poetry when I can, so in that sense I’m always reading/researching/focusing.

What Ruefle says feels overly intentional with regard to my own practice. I’m not running a poem farm, and I don’t feel the need to justify being quiet for a while. I don’t mean to stop or start writing—it just happens. I agree with Percival Everett, one of my favorite writers, that the fact that I write is “evidence that I’m mentally deficient.” It’s possible that that at some point that deficiency could somehow be rectified and that the writing could stop altogether. The book I’m putting together now is called Terminations. Maybe that’s some kind of omen.

In an interview in 2013, you said, "I’ve always had an infatuation with the concept (and the deployment) of the sentence," and later, "the music of this latest book is generated by sentences and the spaces between them." Almost a decade later, is it still the sentence that gets you on the page? Do line breaks and stanzas and open space make their way into the poem later? Can you speak more on this?

I don’t think you can be a decent writer and not be infatuated with sentences. If you’re writing verse, then you’re adding another component, the line, which is, as Allen Grossman says, not natural language but rather an abstract pattern. So I’m always thinking about sentences and lines in relation to one another, except in the case of the book you mention above, To Anacreon in Heaven and Other Poems, in which there are no line breaks. At that time, I was giving myself a break from breaks.

I find it difficult to say exactly how my poems come together—the Philip Guston-via-John-Cage idea that one is working at one’s best (or at one’s luckiest) when one has left the room feels right to me—but I certainly do hit the return and backspace keys quite a lot once I make the move from paper to the computer.

In another interview from 2009, you said you hadn't seen a movie in three years. Is this still an infrequent media for you?

No, I watch movies all the time thanks to home streaming and the fact that I have a nice TV now. In 2009, I had no way to watch movies except by way of DVDs and my laptop, which isn’t a great way to experience a movie.

Right now, I’m rewatching things that I watched on HBO as a kid in the 80s (e.g, The Deer Hunter, American Gigolo). Dredging up my incredibly inaccurate memories of them has been usefully unsettling.

Film aside, it seems that music might be more your medium. What records/songs/albums have you been enjoying as of late? Any decade or genre you really gravitate towards?

I’ve noticed that a lot of people I know have genre phases, but I tend to just have record phases, meaning that I’ll listen to a single record over and over again for a long time. Lately I’ve had Jeff Cowell’s Iron and Ice on repeat.

I’ve also been listening to the latest records by X and the Psychedelic Furs, both of whom I listened to obsessively as a teenager, but neither of whom I’ve ever seen in concert. They’re touring together later this summer, and while I’m sure they’ll mostly play the hits, the new songs are quite good, and I don’t want to do that thing where you just wander off and get another beer when you don’t recognize a song…

I probably listen to Julius Eastman’s “Stay On It” once a week.

Despite your newest collection being barely one year old, can I ask what you're currently working on? It seems that you release collections of poetry every 2-3 years. Does this mean we can expect another book in 2023/2024?

I’m working on a new book called Terminations, which is pretty much done, if “done” means that I’m doing a lot tinkering with little words and punctuation and moving a few poems into, out of, and around in the manuscript.

By my count, you've released eight collections of poetry. At what point does the 'Collected' or 'Selected' begin to be discussed? Book 10? I'm fascinated by those tomes that cover a full bibliography. Diane Williams' Collected comes to mind.

I don’t know. No one’s ever brought it up with me, and it’s not a discussion I would feel comfortable starting.

My sense of these sorts of things is that there are two main motivations for publishing such books, the first being to return to print work that at some point was out of print (e.g., Barbara Guest’s collected poems or the collected and selected volumes of Larry Eigner’s work) and the second being to try to erect a monument that might win some sort of big prize. I’m grateful for the first motivation, as it’s made a lot of lost or hard-to-find poems available to me, but I have no feelings about the second that would be worth communicating beyond those in my poem “Collected Poems” in Nightingalelessness.

If you can, provide a photo of your workspace / writing space or describe with words). What are some essentials while you write?

I have an office on campus where I keep most of my books, but I pretty much use that space for meetings, writing emails, and hanging out between classes or meetings.

I don’t have a dedicated space for writing poems, and I have no habits or rituals except that I tend to write things by hand first and I tend to prefer pencils over pens. I don’t (and can’t) listen to music when I write, and I don’t have a specific time of day that I dedicate to writing. Poetry happens when it happens, and its occasional intrusions are the most varied happenings in my otherwise rather routine-oriented and not particularly “arty” life.

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you choose.

I’m not really a prompt person—there are plenty of poems in the world already, and the idea that I would try to will another one into existence by way of goofing around feels weird to me. I’m not a poem factory and am happy to not identify as a poet when I’m not working on a particular poem.

Of course, I do use prompts in my classes or workshops, but in that scenario, it’s really to show beginning poets how a poem might start with a scrap of language or some metrical pattern that they can’t get out of their head or a sudden association that seems both mysterious valid to them, etc., and that they can build from there, regardless of their not having formulated a hot take on some “subject” in advance. Once you’re comfortable with the idea that a poem might not always (or ever) have its origin in something you already know you want to say, you don’t really need prompts—you just need to pay attention. I’ve found Rita Dove’s “Ten-Minute Spill” (which is in a book called The Practice of Poetry, edited by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell) and all of the prompts in Mary Kinzie’s A Poet’s Guide to Poetry to be excellent teaching tools.

My main poetry “tip” is this: If you’ve gathered some language that gives you a combination of irritation and pleasure—and if you feel like it might all want to Lego together in some way—choose a particular form, start counting syllables and stresses, etc. It matters little if the poem ultimately adheres exactly to that form or that meter once you’re done; the point is to give your mind something it knows it can do (e.g., rhyme, count) and to let some of that confidence and ease leak into the part of your mind that’s trying to do what it doesn’t know how to do.

In closing, do you have any advice for early writers? Or rather, what's something you would have liked to have known when you first started taking your writing seriously?

For me, writing is both painfully real and bewilderingly isolating, and I would say to anyone who experiences it in these same ways that this is okay.

Write to make the thing you make and not for any other reason. And don’t get your writing too twisted up with anything else, particularly something you might someday want to quit (like your job or smoking cigarettes).

Any final thoughts / words of wisdom / shout-outs? Thanks again!

Allen Grossman: “Today, the function of workshops is by and large to regulate art so that it can’t do anything. The civility of the institution (the university) which provides the occasion for the workshop has repressed all useful outcomes.”